As a 10-year England international from 1984 to 1994, Sadie Mason has been involved in the game at all levels for most of her life.

A former GB Students player at the World University games of 1983, ’85 and ’87 and a National League player with London Central YMCA Bobcats and clubs in Edinburgh and Glasgow, she has more recently been a team manager, working with the GB and England Under-18s at seven FIBA European Championships between 2012 and 2018.

Sadie has twice been a national delegate at the FIBA World Congress and is a qualified coach, referee, table official and UKCC basketball coach assessor.

A University of Brighton graduate, former CEO of Basketball Scotland, and now the CEO of Active Sussex, her professional background spans over 30 years in retail finance, plus organisational management and corporate governance, and was awarded an MBE at Buckingham Palace by HRH William – now The Prince of Wales - in 2014 for Services to Sport.

Sadie still has the playing bug, captaining the GB Women’s 50+ medal-winning teams at the World Championship 2019 in Helsinki, and co-captain at last year's European Championship 2022 in Malaga. She has been instrumental in developing a recognised performance level programme for male and female players aged 35+ years (maxi-basketball) to continue playing internationally.

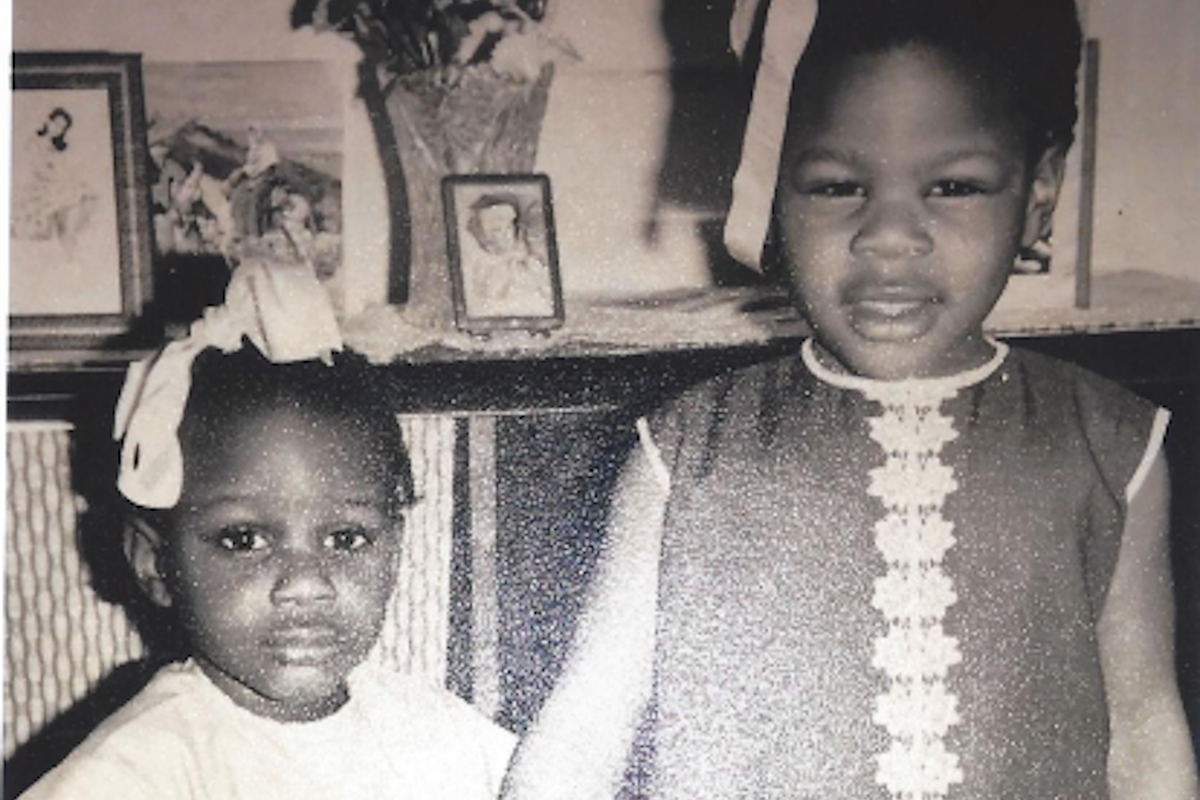

Here, Sadie shares memories of her mum and dad, who were part of the Windrush Generation and her own experiences of growing up in Britain as a child of the Windrush.

When I represented Great Britain or England as a junior basketball player, there was always this undercurrent of black players ‘not really being from the UK’, even within Basketball England or the EBBA as it was then. In other sports like football, I would see and read about fans chucking bananas at the black football players. And at that time, I would ask myself ‘do I really want to represent England?’. I was really proud to wear my country’s colours but it was always in the back of my mind as to whether the people watching me play would really think I was British, and worrying about any abuse I might receive if I performed badly.

At Euro 2020, when Bukayo Saka, Jadon Sancho and Marcus Rashford were subjected to racist online abuse after missing their penalties, I couldn’t help thinking beforehand, ‘please score’, because I knew the abuse they were going to get. How and why is it, in this day and age, that people with non-white heritage still have to find the mental strength to put on the shirt of their national team?

My mum and dad came to Britain from Antigua and were married here in 1958.

Dad wanted to learn how to drive, and my mum was working in service in Antigua; I guess a throwback to the remnants of slave work, which saw black housekeepers working in a large house in service for white owners. They both saw migrating as an opportunity to advance themselves and people were literally talking about the streets of Britain being paved with gold. Obviously, they weren’t.

Their experience was working two or three times as hard to get a job. My mum worked for the London Underground for 25 years as a chef – never once receiving a promotion – and my dad was a warehouseman in a clothes factory in Aldgate East.

A lot of the Windrush generation also found it hard to get accommodation and would normally try and find somewhere to rent that was probably bigger than what they needed and then brought their family over. The notices of ‘No Irish, no blacks and no dogs’ in the windows of rental properties were actually true. They equated immigrants with animals.

I was born in Hackney, but we moved to Newham when I was about four or five and I remember going to primary school because it literally backed onto our house. The area also had a large Bangladeshi community and I have memories of the National Front walking down our street, chanting ‘go back to where you came from’ (well it was actually ‘Blacks and P***s out’) and my dad coming out of the house with a broomstick to stand up to them. I can also recall my mother saying that when you go out, be respectful, be polite and don't cause trouble, because you knew that the police would come down on you. In school, it was the usual inquisitiveness of people wanting to touch your skin, touch your hair, all these kinds of things.

There was an understanding and feeling that you were in the UK to help and rebuild the country, but you felt that you were not really wanted.

We were brought up as Moravian Christians. There are a few Moravian churches in London, but most people held informal prayer gatherings in other people’s front rooms. My parents formed one of the first Moravian congregations in Harold Road in East London and my dad was a minister.

The anecdotes are that they were very religious, but they loved their sport, and so I used to type my dad’s sermons for him so I was allowed to leave the service early to get to London YMCA in time to play national league basketball in central London.

As much as people like to diss church, you got to hang out with your mates, and you got to know your cousins and your family because most of your relatives converged for it. And all the Sunday school outings to Brighton, South End, Clacton and Blackpool. It was just a big community feeling that we were there for one another and to share experiences.

Food was always a big thing, as well at Caribbean parties. The food was just brilliant. I can always remember all the various recipes being cooked on a Saturday morning and having to make ginger beer. But what I remember most is all the different foods and smells from the Caribbean.

In 1972, I stayed in Antigua for a while. It was a few months as my parents had saved up enough money and accrued leave for an extended visit, so me and my sister had to attend school whilst there. Some holiday…it was very strict! The teachers impressed upon us the importance of being educated, because I know, it was something that African-Caribbeans never had when slavery was around as it was denied to them.

There’s no doubt that the Windrush Generation and its children have made Britain culturally richer in terms of food, fashion, music and in many other ways. Notting Hill Carnival and other festivals that celebrate African-Caribbean culture are related to by so many people. They also influenced people to travel more and see the world as a smaller place, and had a hugely positive influence on infrastructure, enabling this country to function in terms of transport and public health, the NHS, etc.

In terms of British basketball and the legacy of the Windrush, people like the late great Jimmy Rogers was one of the early pioneers, certainly in Liverpool and Brixton. He turned a lot of young people’s lives away from crime because they were focused on basketball.

I'm a great believer in sports for social good and lifelong activity, as demonstrated by my master's activity. Many people from the African-Caribbean diaspora have used basketball as a focus for the community and a focus for good, giving people – young and old – a sense of self-worth and self-esteem. I am most definitely proud of my heritage. Basketball has, and continues to serve me well as a child of the Windrush Generation.

.